We may find it difficult to imagine anything more ironic than a President of the United States publicly commemorating the legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in a White House ceremony, while the day before calling for a ban from “shithole” places like Haiti and the entire African […]

Written by Warren Blumenfeld, Independent Writer, Instructor at University of Massachusetts Amherst. (This is a reprint.)

While stunning in its magnitude, no one should be particularly surprised by Trump’s words since he has a deep record of racism coded into his genetic makeup, from a father who participated in Klan rallies, to convictions for engaging in discriminatory housing practices, to statements and policies targeting racially minoritized people and Muslims.

Also stunning in its magnitude beginning the first day Europeans stepped foot on what has come to be known as “the Americas” up until this very day, decisions over who can enter the United States and who can eventually gain citizenship status has generally depended on issues of “race.” U.S. immigration systems have reflected and have served as this country’s official “racial” policies at any given point in time.

Compare, for example Trump’s 2018 statements regarding people from Haiti and Africa — “Why are we having all these people from shithole countries come here?” and people from Haiti “all have AIDS” – to that of Laura Delano Houghteling, cousin of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and wife of the U.S. Commissioner of Immigration — “20,000 charming children would all too soon, grow into 20,000 ugly adults” – in warning legislators to vote against the Wagner-Rogers Bill in 1939, which would have allowed thousands of children, primarily Jewish, to enter the U.S. to save their lives. The bill was killed, and by extension, more than likely were the children who might have been saved.

The “American” colonies followed European perceptions of “race.” A 1705 Virginia statute, the “Act Concerning Servants and Slaves,” read:

“[N]o negroes, mulattos or Indians, Jew, Moor, Mahometan [Muslims], or other infidel, or such as are declared slaves by this act, shall, notwithstanding, purchase any christian (sic) white servant….”

In 1790, the newly constituted United States Congress passed the Naturalization Act, which excluded all nonwhites from citizenship, including Asians, enslaved Africans, and Native Americans, the later whom they defined in oxymoronic terms as “domestic foreigners,” even though they had inhabited this land for an thousands of years. The Congress did not grant Native Americans rights of citizenship until 1924 with the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act, though Asians continued to be denied naturalized citizenship status.

Congress passed the first law specifically restricting or excluding immigrants based on “race” and nationality in 1882. In their attempts to eliminate entry of Chinese (and other Asian) workers who often competed for jobs with U.S. citizens, especially in the western United States, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act to restrict their entry into the U.S. for a 10-year period, while denying citizenship to Chinese people already on these shores.

The Act also made it illegal for Chinese people to marry white or black U.S.-Americans. The Immigration Act of 1917 further prohibited immigration from Asian countries, in the terms of the law, the “barred zone,” including parts of China, India, Siam, Burma, Asiatic Russia, the Polynesian Islands, and parts of Afghanistan.

The so-called “Gentleman’s Agreement” between the U.S. and the Emperor of Japan of 1907, to reduce tensions between the two countries, passed expressly to decrease immigration of Japanese workers into the U.S.

Between 1880 and 1920, in the range of 30-40 million immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe migrated to the United States, more than doubling the population.

Fearing a continued influx of immigrants, legislators in the United States Congress in 1924 enacted the Johnson-Reed [anti-] Immigration Act (“Origins Quota Act,” or “National Origins Act”) setting restrictive quotas of immigrants from Asia and Eastern Europe, including those of the so-called “Hebrew race.”

Jews continued to be, even in the United States during the 1920s, constructed as nonwhite. The law, on the other hand, permitted large allotments of immigrants from Great Britain, Ireland, and Germany.

This law, in addition to previous statutes (1882 against the Chinese, 1907 against the Japanese) halted further immigration from Asia, and excluded blacks of African descent from entering the United States.

It is interesting to note that during this time, Jewish ethno-racial assignment was constructed as “Asian.” According to Sander Gilman: “Jews were called Asiatic and Mongoloid, as well as primitive, tribal, Oriental.” Immigration laws were changed in 1924 in response to the influx of these undesirable “Asiatic elements.”

In the Supreme Court case, Takao Ozawa vs. United States, a Japanese man, Takao Ozawa filed for citizenship under the Naturalization Act of 1906, which allowed white persons and persons of African descent or African nativity to achieve naturalization status. Asians, however, were classified as an “unassimilateable race” and, therefore, not entitled to U.S. citizenship. Ozawa attempted to have Japanese people classified as “white” since he claimed he had the requisite white skin. The Supreme Court, in 1922, however, denied his claim and, therefore, his U.S. citizenship.

Following U.S. entry into World War II at the end of 1942, reflecting the tenuous status of Japanese Americans, some born in the United States, military officials uprooted and transported approximately 110,000 Japanese Americans to Internment (Concentration) Camps within several interior states far from the shores. Not until Ronald Reagan’s administration did the U.S. officially apologize to Japanese Americans and to pay reparations amounting to $20,000 to each survivor as part of the 1988 Civil Liberties Act.

Finally, in 1952, the McCarran-Walters Act overturned the “racially” discriminatory quotas of the 1924 Johnson-Reed Act. Framed as an amendment to the McCarran-Walters Act, the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 removed “natural origins” as the basis of U.S. immigration legislation.

The 1965 law increased immigration from Asian and Latin American countries and religious backgrounds, permitted 170,000 immigrants from the Eastern Hemisphere (20,000 per each country), 120,000 from the Western Hemisphere, and accepted a total of 300,000 visas for entry into the country.

The 1965 Immigration Law, however, was certainly not the last we saw “race” used as a qualifying factor. The Arizona legislature passed and Governor Jan Brewer signed SB 1070, which mandates that police officers stop and question people about their immigration status if they even suspect that they may be in this country illegally, and criminalizes undocumented workers who do not possess an “alien registration document.”

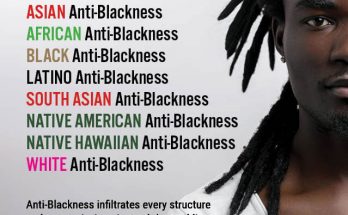

We must all, and that includes members of the Republican Party, condemn Donald Trump in the strongest and clearest terms for his racist statements and actions, which hurt us all and injure our standing around the world. But if we learn anything by our history, Donald Trump is the product of a country, and so are we, founded on the idea of “race”: that socially-constructed and enforced hierarchy of power and privilege.